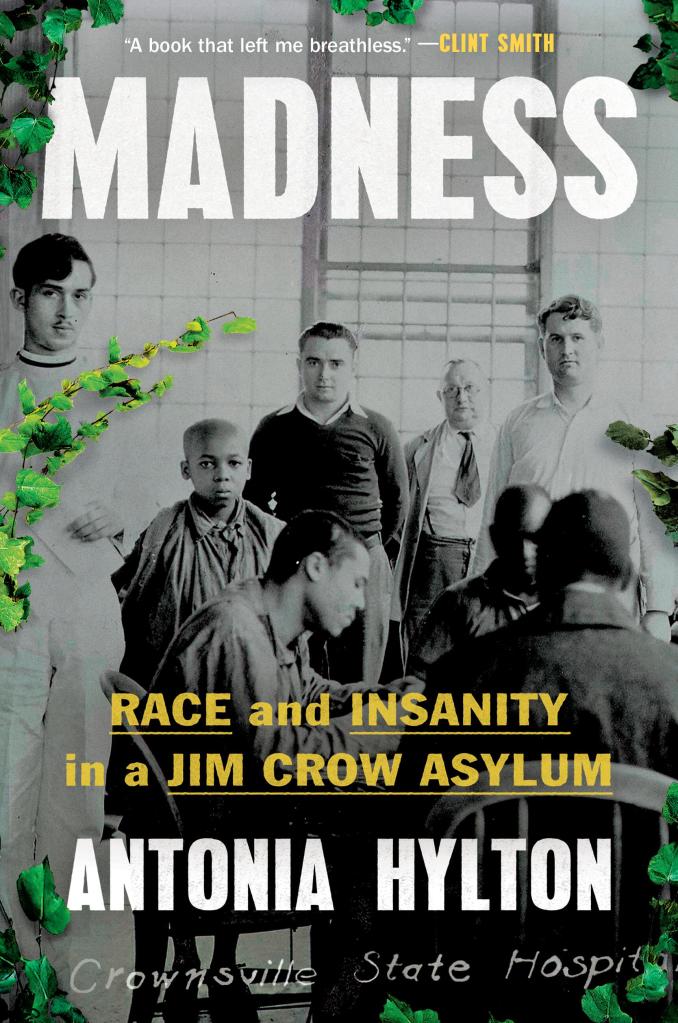

Madness: Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum

- Author: Antonia Hylton

- Genre: Nonfiction, History

- Publication Date: January 23, 2024

- Publisher: Hachette Audio

In the tradition of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, a page-turning 93-year history of Crownsville Hospital, one of the nation’s last segregated asylums, that New York Times bestselling author Clint Smith describes as “a book that left me breathless.”

On a cold day in March of 1911, officials marched twelve Black men into the heart of a forest in Maryland. Under the supervision of a doctor, the men were forced to clear the land, pour cement, lay bricks, and harvest tobacco. When construction finished, they became the first twelve patients of the state’s Hospital for the Negro Insane. For centuries, Black patients have been absent from our history books. Madness transports readers behind the brick walls of a Jim Crow asylum.

In Madness, Peabody and Emmy award-winning journalist Antonia Hylton tells the 93-year-old history of Crownsville Hospital, one of the last segregated asylums with surviving records and a campus that still stands to this day in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. She blends the intimate tales of patients and employees whose lives were shaped by Crownsville with a decade-worth of investigative research and archival documents. Madness chronicles the stories of Black families whose mental health suffered as they tried, and sometimes failed, to find safety and dignity. Hylton also grapples with her own family’s experiences with mental illness, and the secrecy and shame that it reproduced for generations.

As Crownsville Hospital grew from an antebellum-style work camp to a tiny city sitting on 1,500 acres, the institution became a microcosm of America’s evolving battles over slavery, racial integration, and civil rights. During its peak years, the hospital’s wards were overflowing with almost 2,700 patients. By the end of the 20th-century, the asylum faded from view as prisons and jails became America’s new focus.

In Madness, Hylton traces the legacy of slavery to the treatment of Black people’s bodies and minds in our current mental healthcare system. It is a captivating and heartbreaking meditation on how America decides who is sick or criminal, and who is worthy of our care or irredeemable.

As a person who has studied and been employed in the mental health field, I’ve always been a combination of fascinated and horrified in the history of the field. Fascinated to see how far we’ve come, and horrified at the way mentally ill people have historically been treated. There has been a lot of progress in the field of mental health, but it feels like a major step forward when I can compare the treatment of Black people with mental illness from the time of Jim Crow to now.

I read the audiobook, and I didn’t notice that it was narrated by the author until partway through my read. The giveaway was how her voice would sometimes sound like she was fighting off tears, particularly when she was discussing how her loved ones with mental illness had been treated.

The thing that I really liked about this was the way it wasn’t just a narration of the story of Crownsville. Instead, we get a history lesson rolled up into personal stories of both individuals in the author’s family and significant figures of the history of the institution. It made the information recounted here feel even more relatable. There are people in the book who were hospitalized at Crownsville, people who worked there, and the people who actively fought against it at the systemic level.

You see, the Crownsville Hospital was established in Maryland in 1911, at a time when facilities, especially hospitals, were segregated. The ruling in Plessy v Ferguson in 1896 upheld segregation, ostensibly in separate but equal facilities. However, this was just a facade, and it ensured that Black people didn’t receive the same kind of support as white people did. As evidenced by the differences between the conditions at Crownsville when compared to the all-white hospital nearby, there was no separate but equal when it came to treatment and the conditions of facilities.

From the start, the hospital was plagued with issues that only got worse as it became more overcrowded. There weren’t enough employees to properly care for the patients, water quality was poor, patients were at increased risk for communicable diseases like tuberculosis, and people who became inconvenient were hospitalized, including women who wanted to think for themselves. It didn’t really matter much anyway, since there wasn’t any effective treatment to be had until the 1950s.

It was especially difficult to see how innocent people were treated and stigmatized within the community, even by people who worked directly with them. At a time when institutionalization was ever-growing, people were committed for the most trivial reasons. Education wasn’t offered to school-age patients, there was no talk therapy, and nothing in the way of recreation or stimulation.

When reading about people who have been institutionalized, it can be difficult to imagine individuals amongst the masses. But this book brought to life so many patients, staff members, and even activists. There are multiple references to the author’s family history of mental health issues, but she also discusses people that she got to know over her decade of research. And what really stood out to me was how much the field has changed. Services have to be geared specifically towards the diagnosis, including a wide range of areas to address; there is regular oversight of facilities and care; we actually have effective treatment in the forms of talk therapy and medications that have less side effects than initial medications; reduced use of lobotomies and shock therapy; and finally, and most importantly, each person is assessed to determine the context in which their disease developed and their treatment history— including socioeconomic status and stressors, family history, home life, personal experiences, and social factors. This allows clinicians to avoid a cultural bias and develop the most effective treatment plan for them.

Overall, this was a fantastic read. At times it got a little bogged down in details, but those same details prevented this from being a dry and boring read. I love how she individualized a story that could be overwhelming, while also clearly showing how context has been ignored among people of color. In the Jim Crow South, were Black people who were afraid of white people really paranoid? Or were they just responding to the psychosocial factors in play around them? I can’t imagine that anyone with a lifetime of oppressive experiences would also be viewed as mentally healthy when their surroundings had such a harmful and malicious twist to them. I highly recommend this one to anyone with an interest in the history of mental health care, the changes that were made and what created the impetus for them in the mental health system, and to learn how racism has both impacted and impaired mental health for people of color.

Disclaimer: This post contains affiliate links, and I may earn a small commission at no cost to you if you purchase through my links.

Categories: Book Review

Nice post 🎸🎸

LikeLike

Thank you

LikeLike